ABOUT THE AUTHOR WINFIELD COLEMAN

The following was written and prepared by Winfield Coleman, artist, published scholar of American Indian culture and an illustrator of museum catalogs and ethnographic books. Winfield served as curator of the traditional mask portion for the exhibit, Masks of the Americas, which were combined with the contemporary masks created by Becky Olvera Schultz at the Marin Museum of the American Indian in Novato, CA. The exhibit was on display from 11/02/07 to 06/30/08. Contact Winfield Coleman:winfield1@mindspring.com.

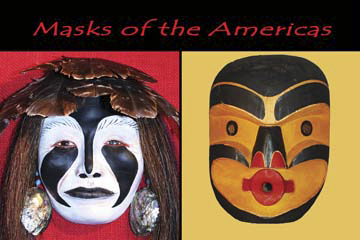

Masks of the Americas, 2007-2008. Official Exhibit Postcard, Marin Museum of the American Indian

INTRODUCTION

“When I create a new mask…I’m a medium…masks are images that shine through us from the spirit world.” Robert Davidson, Haida artist

Masking traditions are widespread throughout indigenous North America. Indeed, the French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss labeled New World cultures as “masking cultures”. Masks can be made of many materials, including paint applied directly to the skin. Wood is the most widely used material, but the ingenuity of Native Americans has been applied to a variety of masks made of cloth, corn husks, leather, gourds, shell, feathers, and metal. The majority of masks combine several materials.

Most masks were and are part of regalia worn in ceremonies, chiefly religious. Such ceremonies may have several features, but most of them possess regalia and a ritual in which are songs and dances. They are not worn frivolously; rather, they represent a transformation of an individual into a representation of the Spirit World to allow him to identify with and control the forces of nature that threaten him. As such, they represent an ancient shamanic tradition of shape-shifting that grew out of the needs of hunting societies, and was adapted to fit the emerging needs of agrarian societies. They also represent kinship, in the broadest sensethe relationship of humans to the natural world–and thus reaffirm the indigenous commitment to seeking balance and harmony throughout the cosmos.

While the masks in this exhibit may be considered traditional, it should be understood that “traditional” culture was but one phase in the life span of that culture; culture change was never restricted to the period of European contact, but spans the lifetime of these cultures, the majority of which date to pre-contact times. Most of these cultures are still extant, responding dynamically to change by folding newer elements into older aspects in an ongoing and creative exchange.

Represented in this part of the exhibit are masks from three important masking traditions in North America, from the Pacific Northwest, from the Eastern Woodlands, and from central Mexico. Masks from the Eastern Woodlands are essentially human, while those from the Northwest Coast frequently represent animals and birds; Mexican masks encompass both. Regardless of what is represented, the essentially spiritual aspect of masks is paramount, they are visions of the Real World of the Spirits, lying just beyond the ken of mortal eyes.

THE NORTHWEST COAST

The western coastline of North America, from Alaska through British Columbia to Washington State, is home to a number of peoples speaking several disparate languages, but with ceremonial, technological, and economic similarities; they can be considered to share definite cultural traits. Their economic base was the abundant sea life of the coastal waters and rivers. The stability of this base enabled the cultures there to develop an elaborate social and ceremonial life unparalleled among hunting and gathering peoples. The great forests provided the resources for a woodcarving tradition second to none. Perhaps most famous for their spectacular totem poles, Northwest Coast cultures also produced a rich and diverse legacy of carved and painted objects.

Among the many objects produced, the ceremonial mask plays an important role in defining and preserving stories, values, privileges, and responsibilities of their owners and makers. The majority of the masks are worn in stylized dances representing incidents from hereditary family myths. These often spectacular performances are seen as prestigious displays of valued prerogatives, and enact the stories that established those prerogatives. Masks were also worn at winter initiations, and during magic and curing rituals performed by shamans.Many masks from this region, however, were never used in traditional functions, having been traded or sold soon after being produced; a practice that began in the early 19th century, and continues to this day.

THE NORTHEASTERN WOODLANDS

The woodlands of the northeast United States and southeastern Canada are home to the Iroquois, a federation of five nations founded around 1570: the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onanandaga, the Cayuga, and the Seneca. These were later joined by the Tuscarora. They refer to themselves as Haudanosaunee. Farmers and hunters, the Iroquois were also feared warriors. The organization of their confederacy was admired by, and influenced, the founders of the United States; and its alliances influenced the early history of this country.

These people maintain a unique society for men known as the False Face Society, whose most striking outward feature is the wearing of masks. Carved from the trunks of living trees, the masks have a striking individuality with strong nose and protruding lips, the face framed with a cascade of two lengths of horse hair. The deep-set eye holes are often framed with metal plates.Masks that are collected in the morning are painted red, while those collected in the afternoon are painted black. Before setting to work, carvers burn offerings of tobacco to the spirits, and entreat them to grant their masks healing powers. The mask features are roughed out in the living tree, usually basswood, then the block is taken home for finishing. If, as often happens, the tree survives, this is considered an auspicious signthe spirit of tree and mask fused.

MEXICO

The masking traditions of Mexico are complicated by many forces that counter the development of local traditions. Although indigenous Mexican economy was and is based on farming, hunting, and fishing, trade has always played an important role. There is considerable evidence that, even before the arrival of the Spaniards, the great centers of development spread their cultural influence over far distant areas, in the form of customs, myths and rituals, and the accompanying paraphernalia. After contact, Spanish influence appeared in different locales at various times, and to varying degrees. Furthermore, communities change over time. Greater mobility now makes it easier for influences to spread, and local traditions are beginning to disappear as a result. But it may be said generally that many indigenous communities exhibited, until recently, an amalgam of native and Hispanic traits, notably apparent in their religious rituals.

Some groups are so Hispanicized that little remains of their aboriginal culture. Living in remote mountainous regions of the states of Puebla and Guerrero, the Nahuas, descendents of the Aztecs, have retained more of their own culture; but even here the native traditions vary dramatically from village to village. The Tarascans have been considerably influenced by Spanish culture, yet retain earlier traits. The Huichols, by contrast, have been minimally affected by outside influences until quite recently.

![]()